Recollections of the Past 30 years pursuing Coelacanths

Jerome Hamlin, creator dinofish.com

In 1953, it was discovered that a fish local Comorians caught from time as a bycatch in their efforts to handline oilfish, and called Gombessa, was actually the same coelacanth "liiving fossil" fish that had been famously trawled off East London, South Africa in 1938. From that time forward, successive governments of the Comoros, first French colonial and later independent, recognizing the specimens were of scientific value, offered a payment to fishermen to turn them over to the authorities. The specimens were then either pickeled, taxidermied, or more commonly placed in fish meat freezer rooms, to await distribution to museums, research facilities, or dignitaries around the world. Knowing Willy Bemis was arriving, I arranged to have one or two of the several available, thawed as he wished to do dissections right there in the Comoros to reduce the weight of materials to be flown out. Mombassa organized a room for the work with a hose to wash down the cement surfaces. I attended and video taped with an 8mm Sony as the dissection took place. I have a fairly strong constitution for this sort of thing, but I recall nausea sweeping over me that left me scrambling for the exit and the warm Comorian night air. Willy finished his work.

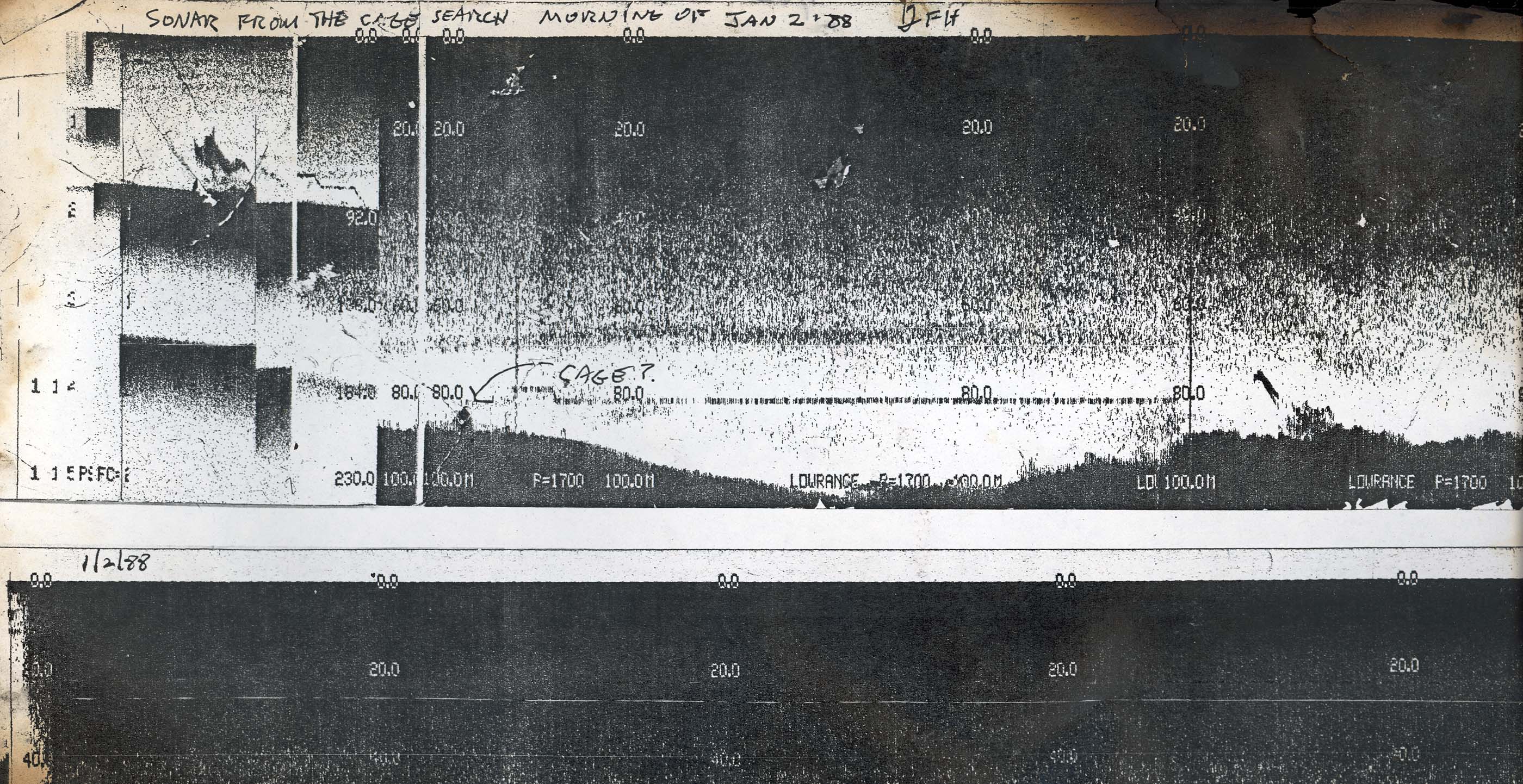

Our Lowrance X-16 sonar on a wooden form that slips over the "Japawa," and later Zodiac hulls, with its two transducers underwater at the tip of an upside down "U."

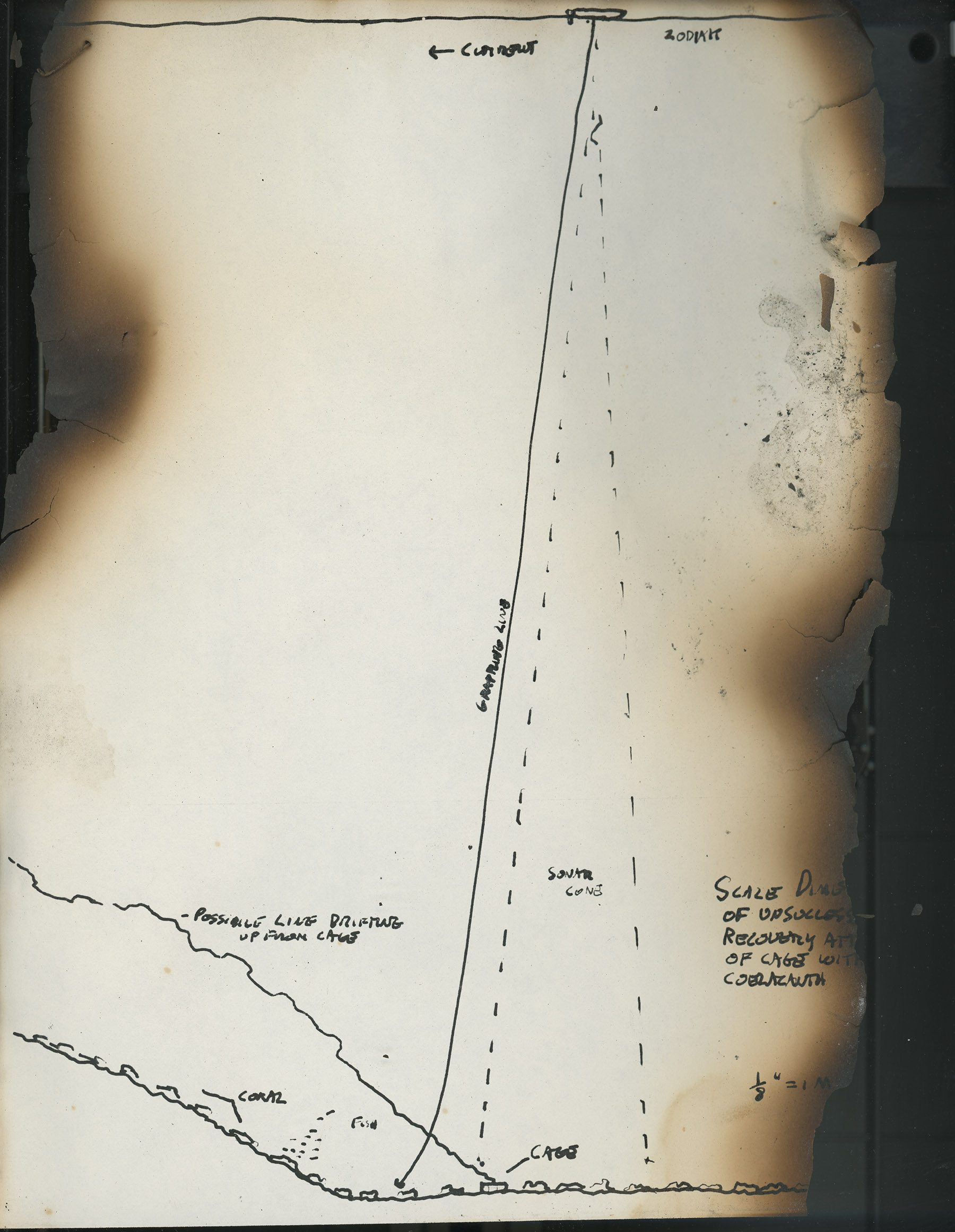

Unfortunately, the submerged cage was far down the coast from Moroni, the capital, and Itsandra Beach, where the previous living specimen was caught. The mechanics at the consulate made me a grappling hook, and the consulate agreed to loan me one of two Zodiacs with 40hp Evinrudes, it maintained for emergency evacuations in case of coups or the eruption of the massive volcano, Karthala which dominates Grand Comoro island. The technician I had spoken with at Lowrance believed the sonar unit should be able to detect the cage on the bottom. What was significant was that this fish had apparently spent very little time on the surface before Jean Louis got it back down in the cage. What I came to call “time on top,” was an important issue, as it became a convincing hypothesis that the main cause of death for caught coelacanths was asphyxiation in the low oxygen warm surface water. Peter and I made numerous trips down the coast from Itsandra, in the Zodiac, searching for the fish in its cage. It was a wild area down there, often rough. There was no portable GPS at that time, and references as to the cage's wherabouts were vague at best. I ran the Lowrance sonar studying every squiggle on the paper printout. Behind us we dragged the grappling hook, trying to avoid bottom snags. Nothing. Was it even there? Had it been pulled up by others when Mombassa fell asleep on watch? And with such a prize, why had no one else from the consulate engaged. Well, it had been New Years Eve, and folks were at parties! We would never know.

I made a sketch to show the actual proportional distance involved trying to snag the cage with a hook from the surface.

Sonar graph showing a possible cage contact.

On the last trip we were caught in a storm on the way back. Monster waves formed off the coast that then smashed down onto the black lava rocks that made up the shoreline. We were forging our way up the coast towards Moroni riding the back edge of these waves. As the storm intensified, forward progress up the coastline became impossible. If we went over the crest of the massive waves we would be smashed to bits on the lava shore. We went into survival mode.